MC#032: Keep the Flame Alive

Plus: How games are the hard work we choose + simulating a Democratic Socialist as President

Hey friends,

This is the 32nd edition of Making Connections, where we take a random (illustrated) walk down tech, fitness, product thinking, org design, nerd culture, persuasion, and behavior change.

If you got this from a friend (lucky you - what good friends you have) why not subscribe and join in the fun?

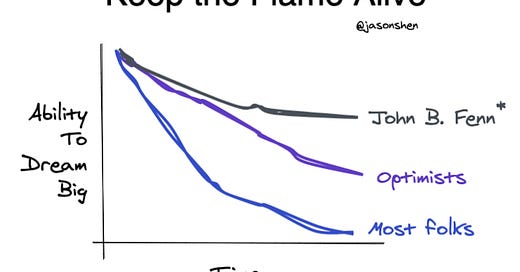

🖼 Visual: Keep the Flame Alive

I don’t want this to come across like a stereotype but I think it’s natural for people to get less ambitious as they get older. It’s understandable: you dream big in your youth and as these dreams don’t come through whether through bad luck, lack of hard work, new interests, it becomes harder and harder to keep thinking that your next big dream can come through too.

But there’s good research that shows that volume (aka shots on goal / times at bat) than age in terms of academic success. John B. Fenn was a late bloomer who eventually became a tenured professor at Yale at the age of 50, where he was ho hum researcher who didn’t produce much of interest. But instead of retiring at 70, he found a new position at another university and kept working on a new chemistry technique he had been playing around with — and that work eventually led to his winning the Nobel Prize when he was 85.

🧠 Thought: Games are Hard Work We Choose

We all enjoy games: whether that’s Among Us, poker, Cyberpunk 2077, basketball, or Beat Saber. But what is a game anyway and why does it matter? I was reminded of the value of games as articulated by Jane McGonigal as a form of hard work—creating, battling, exploring, collaborating—that we choose to engage in because we find it meaningful.

Bernard Suits, the late, great philosopher, sums it all up in what I consider the single most convincing and useful definition of a game ever devised: Playing a game is the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.

When you play a traditional 2D game of Tetris, your goal is to stack falling puzzle pieces, leaving as few gaps as possible in between them. The pieces fall faster and faster, and the game simply gets harder and harder. It never ends. Instead, it simply waits for you to fail. If you play Tetris, you are guaranteed to lose.

I was never a big Tetris guy myself but according to Wikipedia, Tetris is the 2nd best-selling video game franchise of all-time with 495 million units sold between mobile app downloads and physical units sold (behind Mario)

In other words, in a good computer or video game you’re always playing on the very edge of your skill level, always on the brink of falling off. When you do fall off, you feel the urge to climb back on. That’s because there is virtually nothing as engaging as this state of working at the very limits of your ability—or what both game designers and psychologists call “flow.” When you are in a state of flow, you want to stay there: both quitting and winning are equally unsatisfying outcomes.

It’s true. I both love and hate the feeling of wanting “one more round” in a video game where I feel like I’m so close to breaking through.

When we understand games in this light, the dark metaphors we use for talking about games are revealed to be the irrational fears they really are. Gamers don’t want to game the system. Gamers want to play the game. They want to explore and learn and improve. They’re volunteering for unnecessary hard work—and they genuinely care about the outcome of their effort.

This was in reference to the idea that some people see gamers / think of gaming in a negative light, the same to the connotations around hacking.

Games make us happy because they are hard work that we choose for ourselves, and it turns out that almost nothing makes us happier than good, hard work.

When we’re depressed, according to the clinical definition, we suffer from two things: a pessimistic sense of inadequacy and a despondent lack of activity. If we were to reverse these two traits, we’d get something like this: an optimistic sense of our own capabilities and an invigorating rush of activity.

There’s a reason why the App Store as a dedicated slot to games and why so much of consumer technology is driven by the needs of gamers: it’s a fundamentally positive and active experience for most of us. I prefer to game much more than watch TV.

All of this comes from McGonigal’s wonderful book Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. She also has a TED talk that touches on some of these topics.

👉 Check out: Democratic Socialism Simulator

Speaking of games, my friend suggested I check out a game called Democratic Socialism Simulator. It lets you play a progressive President who’s making decisions that need to balance the country’s finances, empower its people, and reduce carbon emissions while ensuring that at least 50% of the electorate supports you so you can win relection.

If you’ve played games like Reign (or used Tinder), it’s similar: you are faced with choices and have to swipe left or right. There are consequences to your choices and as you can see from the screenshot, the issues are ripped right out of the headlines. It’s a little tongue-in-cheek but also thoughtful and pragmatic. A great example of how games can be used to explore real-world issues in meaningful ways.

Get it on Steam, iOS, or Android.

Phew, it’s late and time for me to turn in. Hope your December is coming along nicely. One more full week of work to go!

-Jason

👨🏻💻 About Jason

Jason Shen is a veteran technologist on a mission to rewire our most important algorithms: the ones in our heads. As a serial founder, his companies were backed Y Combinator, Techstars, and Betaworks. As an operator, he’s built products and led teams at Facebook, Etsy, and the Smithsonian. He has bylines in Vox, Quartz, Fast Company, and his TED talk on the future of hiring has been viewed over 4 million times and been translated in 31 languages. A former NCAA gymnastics champion, Jason lives in Brooklyn with his wife, two kettlebells, and many large stacks of books.