066: How Masculine Ideals Affect Resilience

🖼 Lessons Learned (Scotch & Bean) + 👉 Flow Club (focused virtual coworking)

This is the 66th edition of Cultivating Resilience, a weekly newsletter how we build, adapt, and lead in times of change—brought to you by Jason Shen, a 1st gen immigrant, retired gymnast, and 3x startup founder turned Facebook PM.

Hey y’all,

I got through a month of a pretty grueling sprint (both work and life outside work) and excited to take an upcoming week of PTO. It’s a chance for me to decompress, do some reading & writing, invest in longer workouts, and celebrate a friend’s wedding.

I ended up going down a rabbit hole with this week’s thought around how men are affected by our need to perform and adhere to the masculine ideals. I get that not everyone is into that and hopefully next week’s piece is a bit on the lighter side.

—Jason

PS - shoutout to my my wife Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya who just finished a massive 7,750 sq ft mural in Oakland featuring climate change & celebrating black women

🧠 How Masculine Ideals Shape Our Resilience (and How to Make Them Work Better for Us)

Growing up as a boy/man, I was exposed to many ideas and expectations about what it means to “be a man”. I learned that real men are supposed to be strong, brave, tough, aggressive, unemotional (unless expressing anger), capable of violence, rich, street smart, powerful, attractive to women, and willing to sacrifice themselves for the greater good.

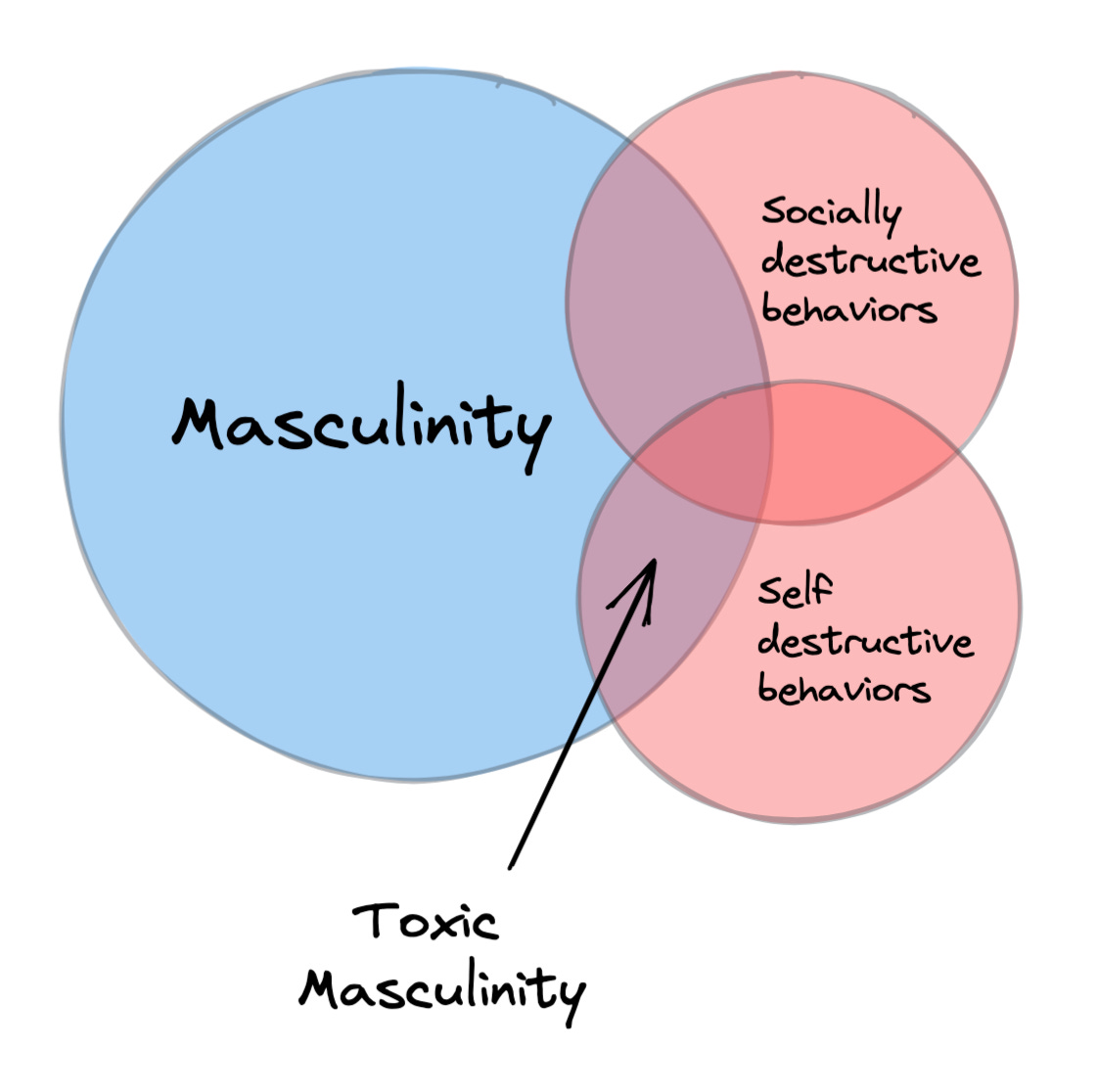

As a society, we are slowly coming to realize that many of these ideas are harmful, not just to others, but to ourselves. Yet not all male ideals are harmful—some can be constructive and helpful to both others and ourselves.

I recently came across the term “hegemonic masculinity”:

In Western and Westernized societies the ideal hegemonic masculinity is treated as synonymous with an identity that is broadly considered to be “macho,” ie, being (to at least some extent) assertive and aggressive, courageous, almost invulnerable to threats and problems, and stoic in the face of adversity. It is thereby viewed as associated with behaviors that display courage and strength and that include refusal to acknowledge weakness or to be overcome by adverse events, while discouraging other behaviors such as the expression of emotions or the need to seek the help of others.

Think about our most beloved superheroes: Tony Stark (Iron Man) and Bruce Wayne (Batman).

Both are fabulously wealthy, powerful, genius inventors who also use violence to hurt others (usually criminals and other villains, but innocent people can be caught in the crossfire). They are often implied to have many sexual partners without a committed relationship, prefer to work alone, and have unresolved emotional trauma that can cause problems for other people in their lives.

This is the masculine ideal writ large.

How does this ideal affect our resilience? Certainly displaying courage and tenacity in the face of adversity is important when seeking to overcome a challenge. It prevents us from collapsing at the first sign of hardship.

But discouraging the expression of emotions or the need to seek help prevents us from discharging the pain and suffering that comes with facing adversity, and getting additional support that may be required to overcome a challenge that proves too much to handle alone.

These ideas are so well known that one TikTok account parodying dumb things men do has 2.3M followers. It’s at once cringey, hilarious, and offensive at the same time.

@Bostonbeaman on Tiktok - satire or reinforcing unattainable ideals?

Why might a man perpetuate these maladaptive strategies of not seeking help or expressing emotion? We aren’t (all) stupid. We can see the value in these things. But sometimes we struggle to enact them. Rachel Alsop and her coauthors argue that its because we would rather preserve our own sense of masculinity (and our status as a man) over our own well-being in material ways.

Because of the unattainability of the masculine ideal, it is argued there is a constant need for men to prove that they are achieving the goals of masculinity and with it a permanent insecurity attached to manhood. Being able to display signs of hegemonic masculinity - for example strength, sexual prowess with women, the ability to consume beer - becomes vital to demonstrate that one is a “real man”.

There is a constant need for men to prove that they are achieving the goals of masculinity and with it a permanent insecurity attached to manhood. Masculinity is presented as a process which needs constantly reaffirming. One’s status as a man is never secure but in perpetual need of validation by other men

Theorizing Gender (2005)

I recently spoke with a young man who felt he needed to be better at approaching women at a bar. This is a very specific way to find romantic partners, but in modern culture it’s been heralded as something a “real man” can do. He expressed that concern directly in our conversation.

I told him that it wasn’t necessary for him to improve in this area unless he personally wanted to. I understood the expectation he was describing and trying to actively rewrite it.

This relates to the unattainability of the masculine ideal: there are too many ways we can be found lacking. This guy felt like less of a man because he wasn’t skilled in this area and perhaps thought he might be judged for it. As Michael Kimmel writes:

We are under the constant careful scrutiny of other men. Other men watch us, rank us, grant our acceptance into the realm of manhood. Manhood is demonstrated for other men's approval. It is other men who evaluate the performance.

Masculinity as homophobia: Fear, shame, and silence in the construction of gender identity. (1997)

There’s a saying that goes around the weightlifting / bodybuilding community that you start out lifting to be more attractive to women but then end up continuing to win the approval of other men. Over my life, many more (straight) men have praised my physique than women.

The need to live up to masculine ideals also depends on other parts of your identity. As an Asian-American man in Western society, I have to face the additional burden of being “less manly” than White or Black men (though Black men can face the other struggle of appearing “too masculine”. As an Asian man, feel the subtle pressure to perform the masculine ideal extra just to be baseline.

Similarly, mens gymnastics has completely deemphasized any skills similar to the leaps or dance elements that the womens gymnasts are lauded for. Dvora Meyers writes about the hypermasculinity of a sport that is often seen by outsiders as being effeminate and how that affects its athletes.

Part of the problem is that these idealized traits might have been more valuable in the past. Historically, women were more likely to reproduce and pass down their genes (saying nothing of whether they truly wanted to do so). Meanwhile, only higher status men had the chance to find a mate, while the most powerful men could mate with many women. One study concluded that in ancient societies around 17 women reproduced for every 1 man.

We could imagine these traits were both genetically selected for and culturally cultivated. Men who didn’t have them weren’t able to accumulate power and have the opportunity to reproduce. But our society has changed and aggressive polygny is no longer the dominant form of mating. We are a more connected, global society and our threats usually require collaboration and cognition rather than mere physical courage or raw strength. Which means it’s on us to transform what masculinity means.

While I know I still operate under some unhelpful masculine ideals, I’ve consciously tried to unlearn a number of them and find ways to resist or rewrite the narrative of what it means to be a real man by prioritizing my wife’s career at least as much as my own, taking on a significant portion of the logistical and household labor of our family and being open with coworkers, friends, and my wife when I’m struggling with something.

It’s on every man, for his own sake if nothing else, to begin to unlearn some of these ideals, because the alternative is to suffer. Studies find that men who identify with or endorse traditional masculine ideals are at higher risk of anxiety, depression, psychological stress, more likely to abuse alcohol and other drugs, and lower levels of intimacy. And yeah, men have been worse about washing hands, social distancing, and wearing masks during the pandemic- to everyone’s detriment.

At the end of the day, there are still many positive qualities that are part of the masculine ideal. Some researchers have tried to view masculinity from this strengths-based approach. Among the strengths they identified:

male relational style focused on shared activities

male ways of caring including use of empathy

a group orientation toward common purpose

the larger societal impact of fraternal organizations

self-reliance

working to be a provider

courage, daring and risk-taking

use of humor

male heroism

By focusing on where masculine ideals connect to resilience, as these strengths certainly do, while working to shift or de-emphasize the more destructive, “toxic” or simply no longer useful aspects of maleness, men can find better results and more fulfillment, and everyone can benefit.

After all, as much as there are biological differences between men and women, there are equally powerful cultural influences. I’ll close by returning to Kimmel, who wrote:

This idea that manhood is socially constructed and historically shifting should not be understood as a loss, that something is being taken away from men. In fact, it gives us something extraordinarily valuable—agency, the capacity to act. It gives us a sense of historical possibilities to replace the despondent resignation that invariably attends timeless ahistorical essentialisms. Our behaviors are not simply "just human nature," because "boys will be boys." From the materials we find around us in our culture—other people, ideas, objects—we actively create our worlds, our identities. Men, both individually and collectively, can change.

Masculinity as homophobia: Fear, shame, and silence in the construction of gender identity. (1997)

🖼 Lessons Learned (Scotch & Bean)

Scotch & Bean: Just two best friends talking about work, dealing with stress, and trying to have a good time.

It’s a shame when we forget all the good stuff we’ve learned a long the way. This is also a way of me saying I really need to do a post on “stuff I’ve learned 1 year into Facebook”.

Follow Scotch & Bean on Twitter: scotch_bean and Instagram: scotchandbean

👉 Flow Club (focused virtual coworking)

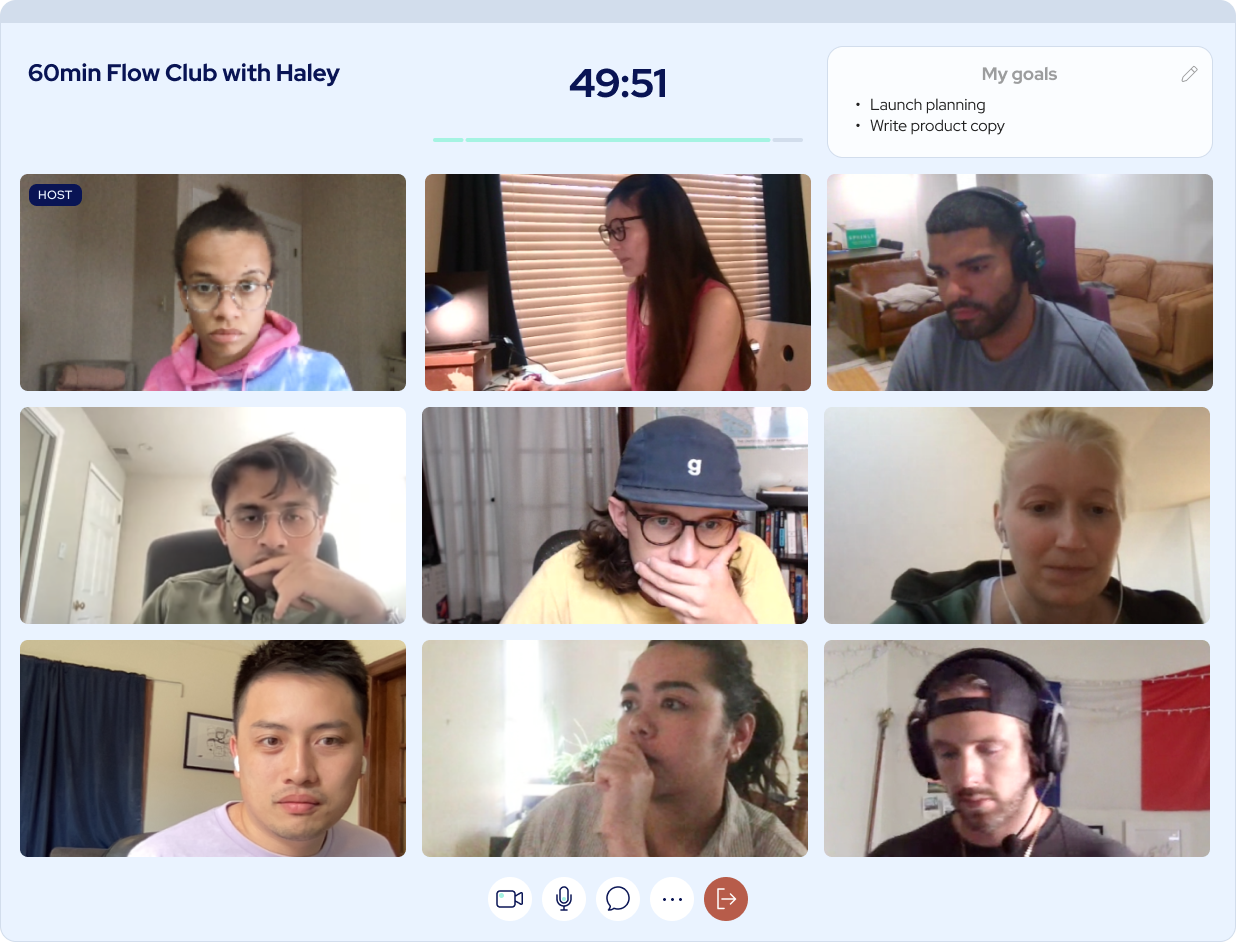

If you’re a freelancer, solopreneur, or otherwise don’t work a traditional corporate job where you have to video conference all the time, you may miss the experience of working silently along side others.

Coffee shops are closed or possible infection sites and you’re having trouble staying focused alone in your apartment. My friends Ricky Yean and David Tran developed a service that lets you tackle a specific creative, strategic, or simply unpleasant tasks in a focused block of time alongside other folks.

The idea is that by having a bunch of people around you deep in work (especially if you have multiple monitors and can keep a view of everyone) you’ll stay in the zone and be accountable to your work. You have declare what you’re doing at the start of the session and give a little recap at the end. I got to beta-test this service when it was in development and they recently hit #2 on Product Hunt. I’m taking the week off for PTO and getting in a session for some of my side projects.

Sign up for the wait list and tell ‘em Jason sent ya!

Flow Club - focused virtual coworking

Like this edition of Cultivating Resilience? Help me reach more people who could use these ideas by sharing it!