Heyo ladies and gents,

This is the 37th edition of Making Connections, where we take a random (illustrated) walk down tech, fitness, product thinking, org design, nerd culture, persuasion, and behavior change.

A bunch of folks joined over the last week after my 25-tweet thread on initial reflections after 6 months as a Facebook PM.

Welcome aboard and if you like the vibes, bring a friend along?

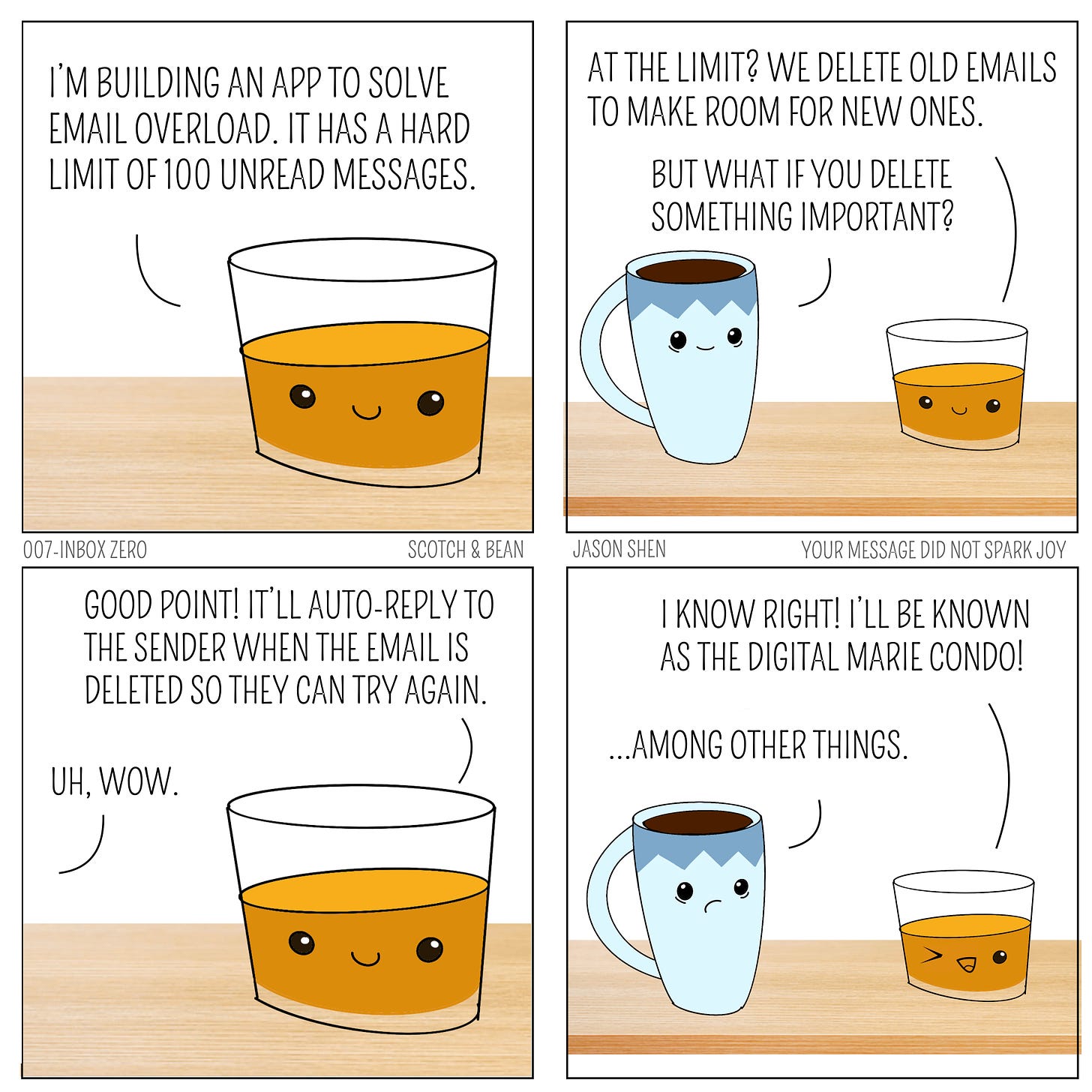

🖼 Visual: Inbox Zero

I know we’ve got Hey and Superhuman, but I think there should be some even more creative ways to handle email overload.

🧠 Thought: The Side Effects of Technology

The Roots of Progress is a blog about the history of technology and the story of human progress. Late last year they published a piece on technology’s side effects. We see that playing out in many aspects of our world right now, including zero-commission trading (Robinhood) and social news aggregators (Reddit). It can all seem very wacky but we need to remember this always happens.

City life provided people with many opportunities for work, commerce, and socialization; but crowding people together in filthy conditions, before sewage and sanitation systems, meant an increase in contagious disease and more frequent epidemics. In the 1800s, mortality was distinctly higher in urban areas than rural ones; this persisted until the advent of improved water and sewage systems in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

It’s easy to forget that for a long time, city life was considered for lower class people. It was for factory workers and people sleeping in tiny apartments, who couldn’t afford a big house in the country. Then cities became the place to experience culture and where the high paying jobs are. Now it feels like the cycle is reversing thanks to this almost year-long pandemic-induced shutdown.

To evaluate a technology, then, we must evaluate its overall effect, both the costs and the benefits, and compare it to the alternatives. (One reason it’s important to know history is that the best alternative to any technology, at the time it was introduced, is typically the thing it replaced: cars vs. horses, transistors vs. vacuum tubes.) …Conversely, a common error consists of pointing to problems caused by a technology and concluding from that alone that the technology is harmful—without asking: What did we gain? Was the tradeoff worth it? And can we solve the new problems that have been created?

The author makes the example of chemotherapy as a technology that fights cancer. Yeah, it makes you feel terrible and nauseous. But it also can keep you alive. And that’s worth a lot. Increasing participation in the stock market might seem dangerous in the short-term, but when only 30% of Americans have money in the market, there needs to be ways to get more people access to a great long-term wealth generator.

No technology is sacred…But if you want to criticize a technology, show that there is a viable alternative, and that it doesn’t sacrifice important properties such as cost, speed, productivity, scalability, or reliability; or that if it loses on some dimensions, it makes up for it on others.

Not every technology is worth the side effects, but side effects alone are not a good reason to throw out a technology. In general, I think outside of perhaps nuclear weapons, we’ve never successfully put the genie back in the bottle after it came out. The main solution to problematic technological side effects is better technology. Culture can make a difference too, but it’s fragile and easily reversible.

Read the whole thing: Technology and It’s Side Effects (rootsofprogress.com)

👉 Check out: “Stress-Is-Enhancing” Mindset

A growing body of research indicates that the experience of stress itself is not necessarily as dangerous as the belief that it harms our health. A 2012 study of nearly 30,000 Americans over an eight year period looked at their beliefs about stress, self-reported stress levels, and mortality rates. The paper found that while higher levels of stress were linked to increased likelihood of dying in a given year, that was only true for people who believed stress was bad for them.

Those highly stressed individuals who thought stress was harmful were 43% more likely to die in a given year compared to those who had almost no stress. But highly stressed individuals who did not think stress was harmful were no more likely to die than the low stress folks.

Here’s further research out of Stanford (Alia Crum) on how stress mindsets affect the performance of special forces:“Following 174 Navy SEALs candidates, we find that, even in this extreme setting, stress-is-enhancing mindsets predict greater persistence through training, faster obstacle course times, and fewer negative evaluations from peers and instructors.” This was true even when accounting for education, body mass index, and other factors.

So how do we activate this mindset? We can understand about how the physiological effects of stress can actually help us. The release of cortisol and adrenaline create energy, stimulate learning, and are a signal that our lives are meaningful. And remind ourselves that our own greatest periods of personal growth often come with a lot of stress.

For more:

Optimizing Stress: An Integrated Intervention for Regulating Stress Responses (pdf)

Stanford Mind & Body Lab: Stress Mindset Manipulation Videos

Alright that’s it for this Saturday. Hope you stay warm (or cool if that’s your situation) and catch you next week.

-J

👨🏻💻 About Me

Jason Shen is an entrepreneur and business leader passionate about technology and human resilience. His past startups have reimagined transportation, recruiting, and gaming; backed by notable investors at Y Combinator, Techstars, and Amazon. As an operator, he’s built products and led teams at companies like Facebook, Etsy, and the Smithsonian. Jason has written about productivity, resilience as well as the future of work in publications like Fast Company, VOX, TechCrunch and has spoken at events at TED, Google and The White House where his ideas have reached millions. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife, two kettlebells, and many piles of books.